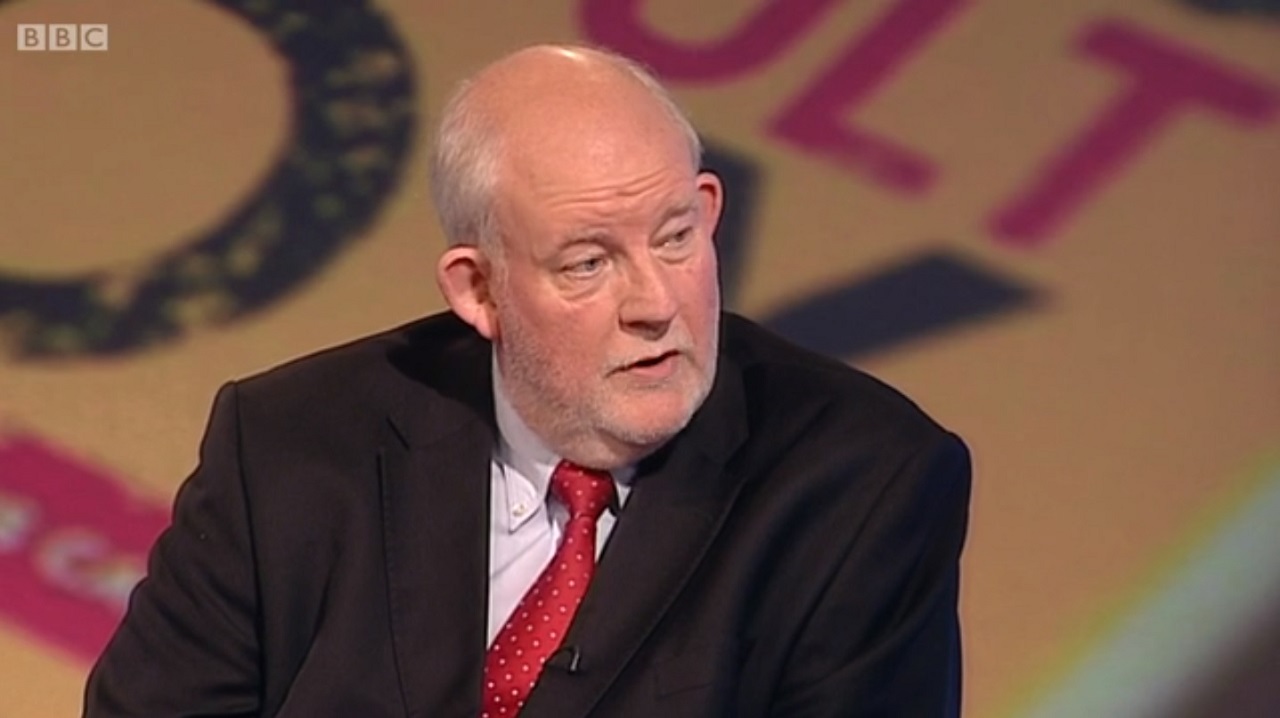

Charles Clarke outlines how devolution to the East could be achieved through local government restructuring and an elected East of England regional assembly.

The outcome of last September’s referendum on Scottish independence has pushed devolution of power in England up the political agenda.

In government Labour thought that directly elected assemblies in the English regions would be the answer.

Now some argue for ‘English Votes for English laws’, whereby Scottish (and possibly Welsh and Northern Irish) MPs would not be allowed to vote on matters which effected only England. Others go the whole hog and argue for an entirely separate English parliament. Whatever their superficial attractions both of these proposals raise problematic issues of principle and practice and neither would devolve power within England to any significant degree.

In parallel, the move towards greater power for Northern cities has gained momentum. The leaders of the 10 district councils in Greater Manchester (whose population is about 2.7 million, with an economy bigger than Wales) have agreed to the government’s proposal for an elected mayor for the whole area. The mayor will oversee policies such as transport and planning, social care and housing and police, towards which the government will transfer an extra £2 billion on top of the £5 billion already spent there by local government. Within the new arrangements the role of the elected Police and Crime Commissioner is unclear. It might be scrapped.

The proposal is modelled on the Mayor of London and effectively recreates the Greater Manchester Metropolitan County, abolished by Margaret Thatcher in 1986, but with less bureaucracy. The government has decided that this change needs no referendum but just the election for the new Mayor, in 2017.

At the same time the idea of elected English regional assemblies lies by the wayside – killed off by the enormous referendum defeat in November 2004 of the proposal for an elected North East regional assembly (77.9% to 22.1%, on a 47.7% turnout).

So where does all this leave the people of Norfolk and other parts of the Eastern region? None of it seems to affect us much. Devolved power to any part of the Eastern region seems a long way away.

If we want to participate in this process of greater devolved power we need to understand the main reason for the 2004 referendum defeat in the North East. This lies in the failure previously to implement across the region ‘unitary’, single-tier local government, responsible for the full range of local government services. Scotland, Wales, London and the metropolitan areas like Greater Manchester have had such ‘unitary’ local government for decades. It is generally regarded as far more efficient, democratically accountable and cost-effective. Services like the NHS and the police are often organised with the same boundaries as these ‘unitary’ authorities, which increases the benefits of partnership working as well as reducing costs.

In the North-East region, before the 2004 referendum, the majority of the population lived in ‘unitary’ areas like Sunderland and Darlington. However part of the population lived in ‘two-tier’ areas where they had both district councils like Alnwick and Easington and the Northumberland and Durham county councils.

The proposition for an elected regional tier of government on top of this two-tier arrangement (even though it only covered part of the region) meant that the regional tier could reasonably be presented as an extra burden which would impose costs, increase confusion and make democracy a good deal more complicated. This greatly weakened the argument for a further regional tier of government.

Despite strong advice to the contrary (for example from me!!) John Prescott decided to hold the referendum before unitary local government had been agreed throughout the region. Consequently the proposal for a third, regional tier of government was resoundingly defeated. The whole movement towards elected regional government in England was halted indefinitely.

The belated 2009 reforms, which created the Northumberland and Durham unitary councils, and abolished the small district councils, now mean that the whole North East region consists only of unitary local authorities. An important objection to an elected regional assembly has been removed.

However that is not the case in any other region of England and the current proposal for an elected mayor of Great Manchester means that any proposal to elect a regional assembly for the North West would be subject to exactly the same objection as in the North-East in 2004 – too many tiers of government.

Moreover it seems likely that the Greater Manchester elected mayor model will spread to the other metropolitan conurbations, Merseyside, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, West Midlands and Tyne and Wear, making elected regional assemblies in those areas equally difficult to contemplate.

These urban developments may well sideline non-metropolitan parts of those regions, such as Lancashire, Northumberland and North Yorkshire and it is difficult to see how devolution to these areas could happen.

However the case for an elected regional assembly could be made in regions without these major urban metropolitan centres. These are the East of England, South and South-West regions.

If unitary local government were to exist across any of these regions an elected regional assembly could be established on the basis of an agreement with central government, similar to Greater Manchester’s.

Such devolution would bring government closer to people and create more local accountability. It would be far more tangible than an English Parliament or English votes for English laws.

It the East of England it would require establishing unitary government where it does not now exist, that is in Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Essex.

It is difficult to establish unitary local government since there are many local political hurdles. But it is a necessary condition for any significant devolution of power to the East of England. And none of the other proposals seem to do anything at all to bring government closer to East Anglian people.

For our part of the world, the combination of unitary local government and an elected East of England regional assembly seems to me to be the only practical way to achieve the highly desirable objective of moving power from Westminster to the rest of England.

Charles Clarke is the former Home Secretary, MP for Norwich South and now a Visiting Professor at the University of East Anglia.

Photo credit: wikipedia

2 thoughts on “Charles Clarke: Devolution to the East”