Lee Jarvis reflects on the British government’s response to last week’s shootings in Sousse.

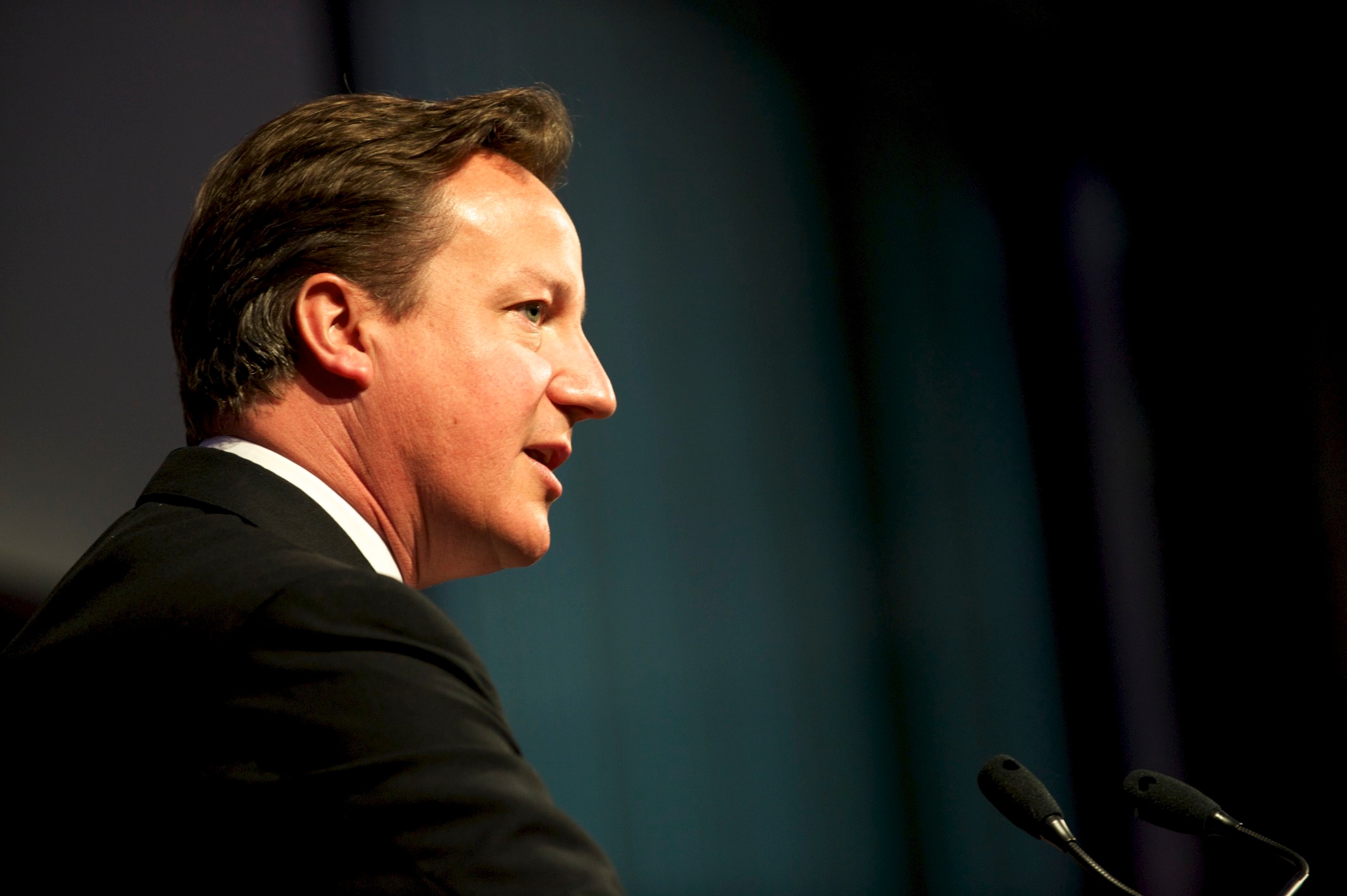

David Cameron’s appearance on this morning’s Today programme offered the most recent articulation of the government’s view on the threat posed by ISIS in the aftermath of last week’s shootings in Sousse, Tunisia. With so much still unknown about those terrible events, it might be worth thinking about the lessons that seem to be being drawn from them, not least because formulations of problems tend to contain within them formulations of responses.

It is immediately striking that Cameron has been very explicit in telling us that he sees the Islamic State – or ISIL, which he prefers – as an ‘existential threat’ to ‘us’ in the West. Understanding anything in these terms, as academics have argued, is something of a high bar. This is because so doing works to position the threat as both urgent and exceptional: as a danger of the utmost seriousness which requires a response of matching fortitude because our very existence itself is threatened. What is interesting in the context of ISIL, however, is that Cameron moves between two quite different understandings of this existential threat. The first is a material and tangible one in which the lives ‘our people at home and overseas’ are being targeted by this enemy. The second is more discursive and focused instead on ‘our values and our narratives’ which – we later learn – involves a commitment to an integrated, successful and multi-racial Britain.

Without in any way trivialising the lives lost in Tunisia (or, indeed, in any other acts of terrorism), it is unclear whether either of these constitutes an existential threat of any sort, other than to the lives of those tragically caught up in the immediacy of particular violences. In the first instance, as John Mueller and many others have argued, countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States (his focus) are capable of sustaining considerable damage and loss of life without crumbling. This has been the case historically, in the form of the industrialised warfare that characterised the early twentieth century. It is also the case in relation to far less dramatic yet more pervasive bringers of harm such as deaths caused by road traffic accidents or preventable diseases. Moreover, as Mueller also notes, we should be rather wary of extrapolations from relatively unusual events – such as, arguably, the shootings in Sousse – because ‘unpleasant surprises’ (in his words) are frequently seen as harbingers of more dangerous and threatening attacks that rarely materialise.

The problem with understanding unusual events as harbingers of still more unpleasant futures is effectively the same as the problem of portraying anything as an existential threat. Both acts readily lend themselves to over-reactions which may prove ultimately counter-productive or even worse. It is – at least – questionable whether recent air strikes in Iraq and Syria against Islamic State targets have succeeded in achieving any long-term strategic goals. The ‘collateral damage’ of these strikes to the lives of civilians and the reputations of Western governments is, unfortunately, less so. Similarly, efforts to link attacks such as in Tunisia to the government’s ongoing campaign against ‘extremist’ groups who do not engage in or even advocate terrorism might be seen as misguided or even exploitative. Whilst exceptional measures such as these are a common part of the logic of securitisation and the urgency it connotes, they raise uncomfortable questions about who – precisely – is threatening ‘British values’, if such values include freedoms of speech, association, and so forth.

Cameron’s attempt to securitize the Islamic State is augmented – in this interview – in two further ways. First is via a set of tropes that are frequently employed in condemnations of terrorism. Describing Islamic State as both a ‘barbarous regime’ and a ‘poisonous death cult’, Cameron combines a (post-)colonial geopolitical imaginary in which the ‘civilised world’ confronts its backward and threatening others, on the one hand. With, on the other, a medical metaphor that resonates with related constructions of terrorism as a cancer and disease, and a hyperbolic caricature (also with potentially racialised undertones). None of these characterisations take us very far in understanding the Islamic State or the threat that it poses. Indeed, all of them work only to demonise ISIS, and to depoliticise and discredit those associated with it. The second augmentation of this securitization is via historical analogy, and an attempt to create an equivalence between the current confrontation with the Islamic State and the Cold War battle against communism. This analogy not only reinforces the danger posed by Islamic State to Britain and its ‘Western’ allies for those listening to the Prime Minister. It also further confirms ‘our’ own moral high ground in this confrontation and, perhaps, encourages us to expect a hard-fought future victory after necessary sacrifices and near-misses.

Lest my interest in the British government’s construction of the Islamic State be taken as an unnecessary distraction from more significant matters, it is worth noting that Cameron himself – like Boris Johnson and others – has shown a real interest in the politics of language in this area. That concern is with the labelling of ‘Islamic State’ thus, and the fear that this moniker might serve to tarnish other Muslim individuals and communities. This is, I think, an interesting discussion, and it is perhaps curious that we don’t regularly ask similar questions about the naming of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, for instance. There is also, no question, that contemporary counter-terrorism initiatives and discourses have worked to present some communities as ‘suspect’ or guilty by their apparent association with groups that wield violence. Exhortations upon Muslims to condemn the latest terrorist outrage wherever it occurs, or indeed the desire to identify, label and reject so-called ‘extremist’ groups, might – in my view – be as significant as the usage of this particular self-identification in these dynamics. Still, if the outcome of this interest is a less dramatized and more patient discourse around the drivers and consequences of political violence, this interest in how we choose to make sense of terrorism is surely something to be welcomed.

Lee Jarvis is a Senior Lecturer in International Security at the University of East Anglia, and a member of the Critical Global Politics research group. His most recent book is Anti-terrorism, Citizenship and Security, co-authored with Michael Lister.