Public transport often doesn’t work for travellers because it’s fragmented, deregulated and operated for short-term profit, writes Rupert Read. A Green transport policy would force operators to coordinate their schedules, integrate multiple transport modes, and entice travellers out of their cars building a real public transport ‘system’.

So if we who travel are to expect greener ways of getting from home to work on public transport, for example, why inspectmainly cost and punctuality, as transport regulators and managers do?

A well-functioning transport system should of course run to time and not cost too much, but greener travel will require a lot more than that.

In 2010, 39% of the UK’s use of energy was attributable to travel and transport. Reducing this significantly is a necessary contribution to reducing the UK’s overall carbon emissions by 80% of the 1990 level by the year 2050, as mandated by the Climate Change Act of 2008.

It’s also entirely feasible – and urgent, because the Act is only a reflection of the harsh realities of climate change: even if we make this reduction in time, we stand barely a coin-flip chance of maintaining a reasonably equable global climate.

Where’s the political leadership to drive change?

Although there’s no strong political leadership (except in the Green Party) or policy framework aimed at reducing carbon emissions attributable to travel and transport, some useful changes in behaviour and policy are taking place.

For example the railways are being progressively electrified, people are choosing to switch to smaller, more economical cars, hybrid and electric vehicles are increasingly popular, and some cities are improving their cycling networks. And crucially, video Skypeing is making a lot of journeys unnecessary.

These changes are welcome, but more needs to be done on both national and local scales. And sadly our national and devolved governments are slow to act to make public transport work better, even on those matters where only they can make it happen.

Travel by public transport is significantly greener than simply hopping into the car (think of the pollution and congestion as well as the carbon footprint) – but how can we expect people to change their travel habits and leave the car at home if public transport regulators and managers don’t inspect the right things?

Whether we’re travelling in order to work, socialise or shop, all but the simplest journeys on public transport are multi-modal – that is, they involve several modes of transport. Perhaps we take a bus or cycle to the station, then take a train, and finish our journey by bus, taxi, tube or a short walk.

But then again, perhaps we can’t – because the bus and train timetables are out of kilter, services are unreliable, there’s a dangerous roundabout you don’t dare cycle across, the cost of that taxi ride at the end is prohibitive, and the bus you need to catch only runs on alternate Tuesdays, or the day’s last service leaves at 2.30pm.

In setting overall transport policy for the nation, how much thought is given to improving the cost, time and general convenience of switching between transport modes? Answer: distressingly little. And if regulators fail to inspect these matters, and require public transport operators to coordinate, for example, bus and train timetables, how can people be expected to change their established travel patterns and habits?

Joined up transport policy, joined up transport

Greens would address this by forcing operators to build a coherent and integrated national transport system in which multi-modal journeys are easy to plan, inexpensive to buy and convenient to take, and local authorities would ensure that cycling is safe and pleasant. This is the only way that people can be tempted to leave the car at home more often.

In some cases, this will require taking assets into public ownership. The railway system is a good example, because a joined-up railway system run for the common good (as opposed to private profit) is just common-sense. And though public ownership of the railways enjoys a high level of public support, only the Green Party is committed to this win-win policy.

Re-regulation is also a powerful policy instrument (which should be applied to buses outside as well as inside London), as are direct economic signals such as provided by congestion charging. This is something of a ‘stick’ to discourage city centre motoring – but there are plenty of ‘carrots’ to be had too, for example:

- Greatly improved information about travel times, interchanges, fares and parking charges for planning a multi-modal journey, as well as real-time information while on a journey

- Integrated timetabling, as found in Germany, where the departure times of bus, coach and local train services leaving a railway station are co-ordinated with the arrival times of longer-distance trains bringing passengers who want to change modes; and that will require …

- … a higher priority for interchanges and transport hubs in infrastructure planning; which will require careful attention by town and city planners, and more investment. Busy interchanges like Clapham Junction and Crewe are far more useful to the travelling public than white-elephant ‘showcase’ schemes like HS2.

- Integrated, contactless payment methods. The growth and development of the Oystercard system, now extended to suburban rail journeys in the London area, and the ability to pay by debit card for all journeys, bring convenience and lower fares to millions of travellers daily. Other conurbations with high travel density would benefit from similar, and ideally compatible, payment systems. As would the counties surrounding London.

- Cycleways that are segregated from dangerous traffic, don’t come to a sudden halt just when you need them most, and follow travel ‘desire lines’. And no, repeat no, ‘Cyclists Dismount’ signs!

We can do it – but if only we elect politicans who want to

None of these elements of a greener transport system is difficult to bring about and all of them are measurable and inspectable. With the vision and political will, of course we can de-fragment our national travel and transport sector.

In the process we can attract more people onto public transport, improve the quality of the travelling experience, and reduce transport emissions. And curiously enough, by putting all this before the short term profits of public transport operators, we can actually grow the entire sector and so make it more profitable, not less.

If what I’ve said so far sounds on the right track to you, then take a look at the report I recently authored setting out a transport ‘greenprint’ for the greater Cambridge area to deal with the city’s very serious traffic and air-pollution woes.

All the proposals outlined above are contained in that document, showing that Greener travel can be achieved – lower carbon, less expensive, better used, more popular and providing a vastly improved service to travellers – provided we elect politicians committed to make it happen.

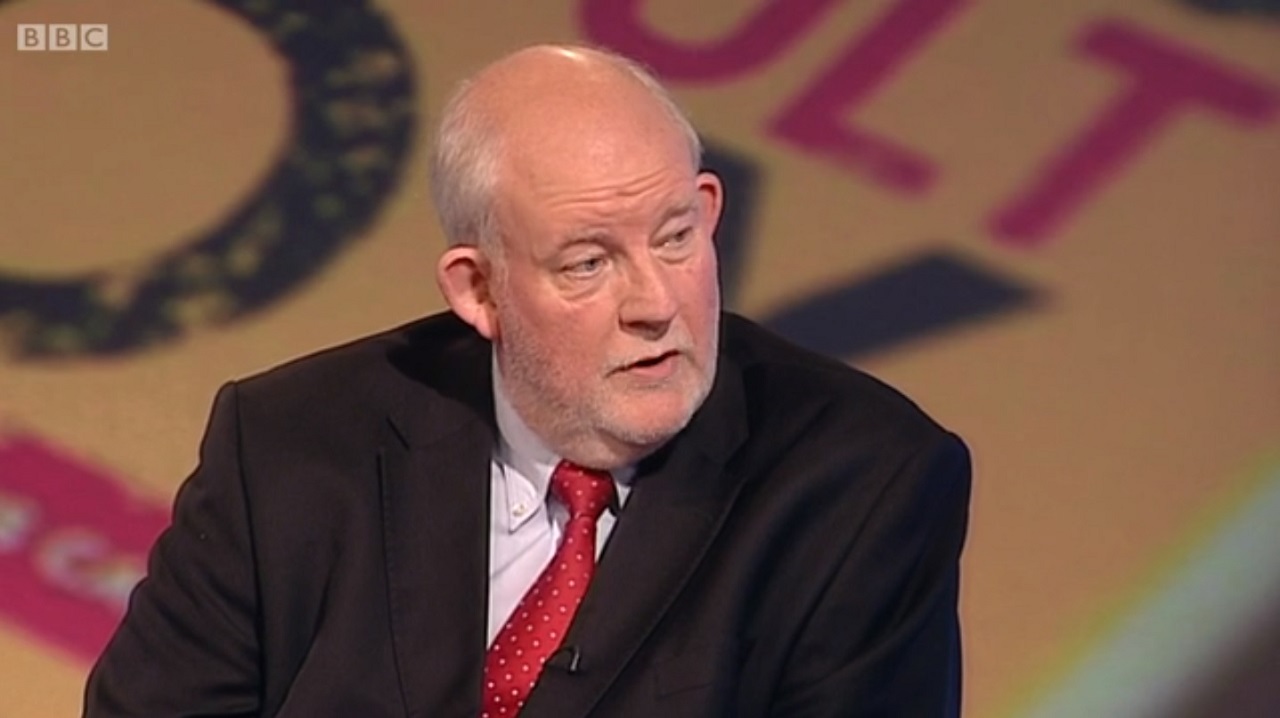

Rupert Read is transport spokesperson for the Green Party of England and Wales, and prospective Green candidate for Cambridge in the 2015 general election – a seat which registered the 3rd highest Green vote in the UK in 2010.

This piece originally appeared on The Ecologist.