Lee Jarvis draws on AHRC-funded research with Lee Marsden and Eylem Atakav to discuss contemporary portrayals of Islam, Muslims and British values.

There are, according to the Muslim Council of Britain – a non-sectarian umbrella body for over 500 Muslim organisations – around 2.7 million Muslims living in Britain today: a figure which is less than 5% of the overall population. This population is a heterogeneous one, and marked by ethnic diversity (with Muslims in Britain self-identifying as Arab, Asian, Black, Mixed, White, and Other), as well as myriad other types of difference relating to religiosity, generation, nationality, political outlook, gender, sexuality, and so forth.

This complex picture, however, is rarely reflected within political, media and public depictions of Islam in Britain today. In one recent opinion poll, for instance, the public was found to greatly overestimate the size of the British public, believing 1 in 6 people in Britain to be Muslim. And, assumptions of homogeneity are similarly widespread. Although the – relatively new – label ‘British Muslim’ attempts to emphasise the way in which contemporary identities are multiple or hybrid, too frequently overlooked is that, as Tariq Modood notes, “The category ‘Muslim’ … is as internally diverse as ‘Christian’ or ‘Belgian’ or ‘middle-class, or any other category helpful in ordering our understanding of contemporary Europe”. This exaggerated, and simplistic, understanding both feeds into and builds on a pervasive sense of threat posed by (certain) Muslims to established British publics, practices, and values. There are at least three dimensions to this perception of threat.

Radicalisation, Extremism, Terrorism

First, and perhaps most prominent, is a widespread construction of Muslims – or, in more nuanced versions, some Muslims – as a significant, often imminent, threat to national security. This understanding is evident in political discourse around ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalization’: labels whose political currency continues undiminished by longstanding academic concerns about their utility. The former British Prime Minster – David Cameron – for instance, introduced his government’s new five year strategy on extremism in a high profile speech in July 2015, by arguing:

What we are fighting, in Islamist extremism, is an ideology. It is an extreme doctrine. … At its furthest end it seeks to destroy nation-states to invent its own barbaric realm. And it often backs violence to achieve this aim – mostly violence against fellow Muslims – who don’t subscribe to its sick worldview.

David Cameron’s successor as Prime Minister – Theresa May – employed similar language in the aftermath of the June 2017 attack on London Bridge, arguing this event was connected to earlier attacks in Manchester and beyond by “the single evil ideology of Islamist extremism that preaches hatred, sows division and promotes sectarianism”. Both leaders focused their attention on ‘extreme’ versions of this religion, and in so doing, invoked a longstanding distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslims. Yet, their collocation of Islam with extremism perpetuates the idea that the former embodies – or, at least contains within it, a national security threat to Britain as a modern, secular, liberal democracy. Such a framing, as authors such as Stuart Croft have shown, is widespread, going far beyond political elites to include media organisations, individual journalists, university academics, public intellectuals such as novelists, and indeed ‘ordinary’ citizens.

Integration

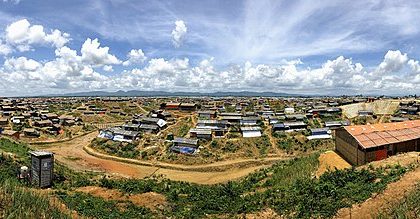

A second aspect of this sense of threat is found in presentations of Islam – or Muslim communities – as resistant to integration within a wider multi-cultural society. Here there are longstanding fears that Muslim communities have chosen to live in isolated or self-segregated ‘ghettos’: speaking, learning, worshiping, working and leisuring largely apart from other populations. The United Kingdom Community Engagement Forums, for instance, were established in October 2015, as part of the Prime Minister’s aspiration:

… to build a national coalition to challenge and speak out against extremists and the poison they peddle. I want British Muslims to know we will back them to stand against those who spread hate and to counter the narrative which says Muslims do not feel British.

Such concerns around the self-isolation of Muslim communities are also evident in the introduction of measures targeting religious schools for fears that they serve as ‘incubators’ of isolation. As David Cameron told his Conservative Party conference at around the time of the introduction of the Communities Engagement Forum:

There are parts of Britain today where you can get by without ever speaking English or meeting anyone from another culture. Zoom in and you’ll see some institutions that actually help incubate these divisions. Did you know, in our country, there are some children who spend several hours each day at a Madrassa? Let me be clear: there is nothing wrong with children learning about their faith, whether it’s at Madrassas, Sunday Schools or Jewish Yeshivas. But in some Madrassas we’ve got children being taught that they shouldn’t mix with people of other religions; being beaten; swallowing conspiracy theories about Jewish people. These children should be having their minds opened, their horizons broadened … not having their heads filled with poison and their hearts filled with hate.

Particular fears around Sharia Law feature repeatedly in discussions such as these; especially concerns that such laws discriminate against women or compromise the long-established ‘rule of law’ principle by which all citizens are subject to the same legal treatment. Such concerns were seen as so significant that they led to the launch of an independent review into the use of Sharia Law in Britain in May 2016, under a panel of experts including academics, legal professionals, and theologians.

Violences and Violations

A third aspect of this multi-faceted construction of Muslims as a threatening ‘other’ to British lives and values is more complex, and concerns anxieties over the threat that some Muslims pose to their (vulnerable) co- religionists. Such anxieties are frequently gendered, focusing in particular on violences against women. Most serious, here, might be issues around so-called ‘honour killings’ and female genital mutilation in which women’s bodies are harmed – at times to the point of death – by others. Yet, practices such as these are seen by many to have cultural rather than religious origins – and occur in communities of distinct faiths and backgrounds – as demonstrated by a recent complaint against the Daily Mail tabloid newspaper that was upheld by the British Independent Press Standards Organisation. This popular, right-leaning newspaper – seen by many critics as xenophobic and Islamophobic – was admonished for its use of the phrase ‘Islamic honour killing’ in a news story, and subsequently amended its headline, clarifying: “We are happy to make clear that Islam as a religion does not support so-called ‘honour killings’”.

Similar impressions around the pervasiveness of violences or discriminatory practices within Muslim communities are evident in the attention that is given to ‘jihadi brides’, ‘forced marriages’ and – more controversially – practices such as gender segregation (for instance, in schools or places of worship) or head coverings. The widespread association of Islam – or Muslims – with such practices, is significant because it risks diverting attention from dissenting voices or counter-examples within Islam itself, as well as from similar practices in other religious or cultural communities. Depicted in this way, Islam stands accused either of a failure to adapt to modernity and its social, political and cultural mores relating to women’s rights and gender equality. Or, on the other hand, of being a great faith having been perverted by prominent, charismatic interlocutors with their own interests. Against such a background it is, perhaps, unsurprising that a March 2015 survey found 55% of British voters to believe that there exists “a fundamental clash between Islam and the values of British society”. In the same survey, in contrast, only 22% of voters believed Islam and British Values to be “generally compatible”.

Conflict?

These three depictions of tension between Islam and British values or society have different subjects of concern, ranging from national security (in fears around radicalisation, extremism, and terrorism), inter-communal relations in a multicultural society (in fears around integration), and the safety or well-being of vulnerable Muslims (in fears around cultural norms and gendered violences). In practice, however, they often blur into one another, further compounding this sense of conflict. Nowhere is this clearer than in the United Kingdom’s counter-extremism agenda: the Prevent Strategy. This Strategy has been widely criticised for confusing governmental priorities relating to security and integration, which combines policing initiatives with work with communities and local organisations in its attempt to respond to terrorism’s ideological challenge, while deterring individuals from being drawn into terrorism.

These fears – whether individuated or combined; whether in media headlines, government strategies or popular culture – suggest that there exists an essentialised conflict between Islam and its practitioners, and ‘British values’. Where the former is conservative, traditional, even barbaric; the latter – typically understood as something like “democracy, rule of law, equality of opportunity, freedom of speech and the rights of all men and women to live free from persecution of any kind” – is liberal, modern, and civilised. The result is a troubling dynamic in which (some) UK-based Muslims are simultaneously demonised – as an actual or potential threat (whether to national security, the British ‘melting pot’, or, indeed, other Muslims) – and infantilised – as actual or potential victims. This not only homogenises a population of considerable geographical, cultural, national, demographic, political and other diversity. It also reinforces established Orientalist ideas and arguments, identifying all Muslims as “at risk of being risky”.

British values

Establishing and measuring the social impact of these dynamics is difficult. Because of this, there has been a temptation – amongst often well-meaning researchers – to speak on behalf of ‘the Muslim community’, and how it has been affected by contemporary developments in security politics. One recent attempt to do something more than this has been the ‘British [Muslim] Values’ research project which has sought to capture public understandings of the relationship between Islam and ‘British values’ or society by asking members of Muslim communities to make their own short films on this theme. This effort to share personal, biographical experiences from across these communities paints a far more variegated picture of the place and ideas of Muslims in British society today than that suggested in some of the caricatures discussed above. This short clip, for instance, speaks not only to the diversity of Muslims in Britain today, but also a common understanding – across this diversity – of a fundamental compatibility between ‘British values’ and Islam.

This understanding of compatibility was something we encountered in a number of different communities across our research in the Eastern region of England. As one Muslim man who participated in our research argued: “I don’t see any conflict … we are more similar than we have differences”. Indeed, some Muslims with whom we spoke went further still arguing that converting to Islam actually shed more light on fundamental British values, making them conscious, individually, of values that they had previously taken for granted. In the words of one man living in Norwich, for instance: “Certainly, from my own perspective, once becoming Muslim I understood more about British values, more about my culture. Decency, honesty, integrity, decorum. All aspects of traditional British being were recognised for the first time”.

A number of non-Muslim participants in our research reported a similar view, drawing similarities between Muslim values and those associated with British life: “I think a lot of British core values do tie in with Christian values don’t they, in their true form. But then the same with Muslims, we’ve all got the same sorts of ideals haven’t we, it’s just how that gets translated into real life, real situations”. While we did encounter some accounts of tension between Britishness and Islam, especially in the area of gender relations – “I think perhaps Muslims’ ideology has a slightly different idea of what relationships between the sexes should be than our society which is basically secular” – many Muslims and non-Muslims are as exorcised by the continuing demonisation and stigmatisation of Muslims. In the words of one Muslim woman, for instance: “politicians, they only focus on Islam when there is a bomb here or a bomb there and they use it as a tool to attack certain people, certain communities”. Importantly, as a non-Muslim man argued, there are also real issues of double standards here given media and political reluctance to use religious labels in the description of other campaigns of violence experienced in Britain in recent times:

“Non-violence is very important to Islam. That seems to have got lost in the media’s perception where they seem to conflate terrorism/extremism with a religion, and there are lots of terrorist extremists of lots of different faiths, but it doesn’t seem to stick to their religion. Think about the IRA [Irish Republican Army] when I grew up, when it was really quite scary the bombings on mainland Britain by the IRA. People didn’t say that’s Christian terrorism, but those people were Catholic, Christians.”

Looking forwards

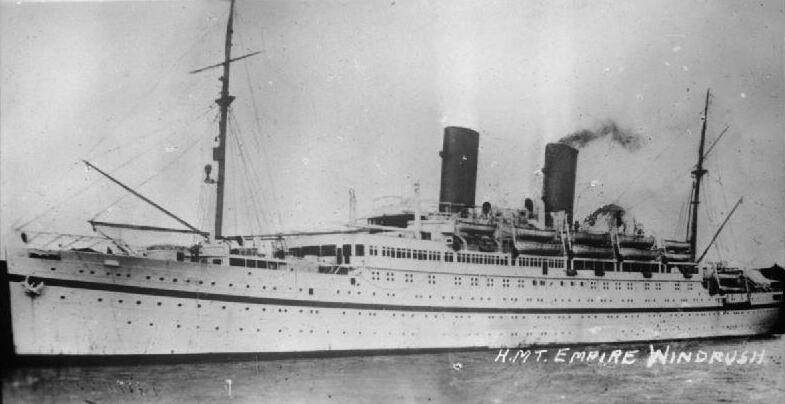

As we have argued, there remains a lot of work to be done in the ways in which Islam – and Muslims – are constructed or spoken about within British society today. Each of the fears mentioned above draws on long-standing anxieties not only about Islam (although these go back hundreds of years), but also about the state of multiculturalism in Britain today. Whether British or otherwise, Muslims are still, far too frequently, depicted as ‘other’: as outsiders within British society. Because of this, anxieties around Islam become entangled with a whole range of security concerns – from radicalisation and terrorism through to issues around immigration and job security. Once a community – even one as diverse and variegated as the Muslim community in Britain is – becomes widely presented as different to the rest of ‘us’, it becomes easy to see its members as the source of many of our social and political problems.

There are, though, reasons for optimism here – not least in the examples of public willingness to contest this sense of otherness when thinking about ‘British values’. Looking forward, it is important to build on these, and there are three ways in which we might do this. First, it is critical that we continue to challenge simplistic stereotypes of Muslims as terrorists-in-waiting or, indeed, as any other type of threat. One way of doing this is simply to engage with the numbers, and to continue to highlight the ‘real’ scale of these issues, which is typically far smaller than often believed (this is not the same as portraying them as unimportant). Second, is to show how Muslims have been depicted as a problem: to look at the words, images and so forth use by politicians, newspapers, filmmakers, or others when they discuss Islam in Britain today. And the third thing we can do, is to try to tell other, different, stories about Britain and Islam: to shift the discussion away from security concerns, and to allow space for Muslims to share their own experiences about life in Britain today. Doing this may help to combat the disproportionate focus on Muslim violences and intolerances. It might also help to combat some of the stereotypes that continue today.

Lee Jarvis is Professor of International Politics at the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. He is author or editor of 11 books and over 50 articles or chapters on the politics of security and terrorism.

This piece was originally commissioned by, and published on, Limes Geopolitics.

Photo credit: iDJ Photography.