It is ten years since the attacks in London on 7 July 2005. Lee Jarvis provides seven reflections on those events, their aftermath and consequences. He concludes that anniversaries create as much as recall memorable events.

-

‘Spirit of the Blitz’.

My own memory of watching the coverage of 7/7 unfold is dominated by two things. First, is the image of the bus that was targeted in Tavistock Square, and quickly became the most recognisable symbol of the attacks. The second is the ‘spirit of the Blitz’ language that seemed to emerge very quickly in their aftermath (if my memory is accurate – on this, more below). The latter has no doubt stuck with me because I was trying to write a PhD at the time on constructions of time and history in the so-called ‘war on terror’. More than that, though, it seemed a strained metaphor to me even then (what the ‘spirit of the Blitz’ meant beyond a sense of courage and unity wasn’t immediately obvious to me); one that was simply too transparent in its intention to create an impression of collective identity. Obviously the language we use to frame events such as ‘7/7’ (itself a political label) matters a great deal, and that is true for how we situate such events historically (‘9/11 was the new Pearl Harbor’; the next cyberattack could be a ‘digital Waterloo’, etc.) as well as how we position them morally (terrorism as the epitome of evil, cowardice, or barbarism, and so forth).

-

‘Terrorism’ is never an objective label

So much ink has now been spilled on the meaning of terrorism that the prospects of any consensus seem as distant as ever. One recent survey found over 250 different definitions within academic and political sources, no doubt there are many more out there waiting to be discovered or produced. My own view is that ‘terrorism’ is never an objective term that can be applied accurately or definitively to particular acts of violence. It is a term that emerged at a particular historical juncture (the French revolution), has evolved in multiple ways since to mean something quite different (the now-dominant association of the word with violences against civilians by non-state actors), and – clearly – means different things to different people (otherwise so much ink would not have been spilled!). ‘Terrorism’ is a component of specific political discourses which create violences as such rather than describing them. It is neither correct or incorrect, in my view, to describe 7/7 as an act of terrorism, at least in an absolute sense. The same as it is neither correct nor incorrect to ignore state atrocities (perhaps Dresden or Hiroshima) within any discussion of the history of terrorism. What does matter is to ask how the label ‘terrorism’ is applied to some acts – such as 7/7 – and not to others, and to try to think through what assumptions and exclusions such labels and histories rely on and (re)produce.

-

The threat of terrorism in the UK remains fantastically small

If we stick – for now – with the types of violence routinely described as ‘terrorist’, the UK remains, it is safe to assume, a fantastically safe place to live. A couple of caveats are, however, in order here. First, those of us outside of the intelligence and security services will rarely have access to the necessary knowledge to speak definitely about this. As Marc Sageman provocatively put it in a recent contribution: academics understand everything about terrorism, but know nothing because of their distance from intelligence analysts. Second, unusual and unexpected events do on occasion occur, and terrorism’s power is not necessarily reduced by its rarity. As the IRA spokesman famously put it – ‘we only have to be lucky once’ – bearing in mind all the caveats about the meaning of terrorism above. Third, matters of threat and risk – just as matters of definition – are also discursive, and involve the production of knowledge about futures to come that rest upon particular claims to authority and specific types of logic. So, to say the threat of terrorism remains fantastically small is already to concede much to a particular conception or dispositif of threat and of risk.

With all that said (!), we do know that death and other forms of harm from acts labelled ‘terrorist’ are far outstripped by any number of far more mundane sources of violence, especially for those of us living in the global North. The reasons for this are, no doubt, complex, but probably involve the work of police and other agencies, the gap between intentions and capabilities amongst ‘wannabe terrorists’, or the fact that many would-be terrorists are motivated by something other than mass casualties. Of course, this may all be missing the point. One could perhaps argue that the terrorism threat refers to the symbolic threat it poses to sovereignty (as Charlotte Heath-Kelly does in her chapter here), or its challenge to liberal democracy, multiculturalism and so forth. This, however, is not where terrorism discourse tends to focus, and we might also note that the instances in which terrorism has proved ‘successful’ in fundamentally challenging established political authority are limited (although have been argued to include Algeria, Colombia, Lebanon and Palestine).

-

UK Counter-terrorism since 7/7: Plus ca change?

Despite the (potentially) limited threat of terrorism, the years since 7/7 have witnessed the introduction of considerable new counter-terrorism powers: many of which have since been removed or changed, including by appeal. Despite the prior existence of a considerable piece of legislation – the 2000 Terrorism Act – as well as new powers introduced after 9/11, the UK has significantly uprated its counter-terrorism capabilities in the last ten years. This has included, amongst other things, extending the maximum period for detention without charge to 28 days, the creation of new offences around the glorification of terrorism and terrorist preparation, a new TPIMs regime, and significant investments in counter-radicalisation programmes associated with the Prevent stream of ‘CONTEST’. Whilst these and related measures have been much discussed and critiqued, it is important to note – as Andrew Neal amongst others has argued – that there are historical patterns at work here. The UK’s historical record is one of repeatedly responding to terrorist attacks with rapid and arguably over-exuberant legislation justified as merited by exceptional circumstances, but which tends to become normalised over time.

-

Counter-terrorism powers have had profound consequences for citizenship

Much discussion remains to be had on the specific purposes of counter-terrorism policy. This is not as straightforward as we might think: the UK’s usage of proscription (which bans terrorist groups from the UK), for instance, is explicitly justified on symbolic, strategic and other grounds by the Home Office. One thing that counter-terrorism powers undoubtedly do, however, is impact upon citizenship, although not in a straightforward way. In some of my work with Michael Lister on this, we’ve been speaking with different UK communities about their own understandings and experiences of counter-terrorism policy. Our findings suggest that counter-terrorism powers impact not only upon civil liberties, but also upon people’s sense of Britishness, their feelings of obligation toward the UK, and their ability and willingness to participate in social and political life. How they do this, moreover, varies quite widely, with individual and collective identities and experiences of the state appearing to come into play here. Moreover, although much recent research has – understandably – focused upon Muslim communities, non-Muslim individuals with whom we spoke often felt directly targeted by recent UK counter-terrorism initiatives. As a woman in Swansea put it to us:

‘I’m being watched, I’m being searched, I’m a target group, I’m not safe’ (Swansea, Black, Female)’

-

Radicalisation, Politics and Religion

Much political discourse in recent years on terrorism has focused on the notion of ‘radicalisation’. As Arun Kundnani, Akil Awan and others have argued, there are real problems with this term, not least that it implies a linear, homogenous pathway to violence that is, it seems to me, entirely unsubstantiated by empirical evidence. Discussions of radicalisation put emphasis on two apparent causes of terrorism, neither of which appear particularly helpful: psychological vulnerability and religious fervour. The first is potentially problematic in that it recreates myths of the ‘terrorist’ as madman (or madwoman) or brainwashed dupe. The second is problematic for downplaying potentially significant political factors, and because the term is overwhelmingly applied to Muslims. Although discourses of radicalisation imply that terrorists are made and not born, they also imply that all Muslims are potentially suspectible to the process, and – therefore – potentially suspect.

This implication is, of course, largely a nonsense. Events such as 7/7 have numerous causal threads many of which may not be identifiable. But, violences of the sort we now label ‘terrorist’ have been committed by individuals attracted to any number of the world’s religions or ideologies. The constant demand that Muslims explain or condemn particular interpretations of that faith is both unpleasant and absurd, given that similar dynamics do not play out when violences are committed by Christians, right-wing fanatics or others. That it even feels necessary here to note that the majority of the UK’s – or the world’s Muslims – abhor violences such as 7/7 itself speaks to the hegemony of this discourse.

-

Anniversaries create as much as recall memorable events

Ten years on seems an obvious place to reflect on the events of 7/7, and their consequences for individuals, and communities and so forth. There is nothing, I think, inappropriate in so doing, although it is important to remember that memories are never neutral. Which people we remember, and how we narrate and give meaning to their lives and deaths is inevitably partial in the sense of being both incomplete and perspectival. And, any effort at commemoration or remembrance necessarily involves acts of forgetting which take place both by downplaying particular aspects of an event (perhaps British foreign policy in this case?) and refusing to acknowledge others (perhaps the consequences of the deaths of the attackers for their families?).

This partiality becomes particularly obvious when memory is explicitly tied up with discourses of patriotism, nationalism and simplistic binaries between good and evil or freedom and fear. But, minutes of silence, political speeches and other ‘memorial work’ – such as blog posts like this – serve to confirm the impression that we have witnessed something worth remembering. All lives, I imagine, merit marking and remembering for someone. That we (can?) only do this for some is, I think, where politics enters the arena of memory.

Lee Jarvis is a Senior Lecturer in International Security at the University of East Anglia.

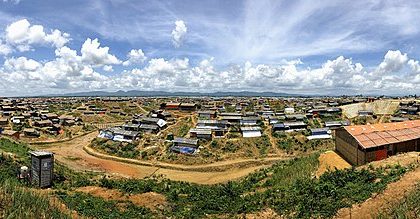

Image credit: wikipedia