On tonight’s Newsnight, Chris Hanretty runs the numbers on “economic voting” — the tendency of voters who are doing well economically to vote for incumbent parties. This post describes the data — which you can download here.

“Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”

That was the question Ronald Reagan asked American voters in his successful 1980 presidential campaign. Reagan was betting that voters felt worse off, and would punish the incumbent, Jimmy Carter.

More than thirty years later, the Conservatives are making a similar gamble. They’re betting that voters will realize that incomes are recovering, and vote for Conservative candidates as a result.

The gamble worked for Reagan in the eighties, and for Clinton in the naughties. But will it work for the Conservatives this year – or will this end up being a voteless recovery?

The question of economic voting can be approached at two levels — nationally and locally.

Nationally

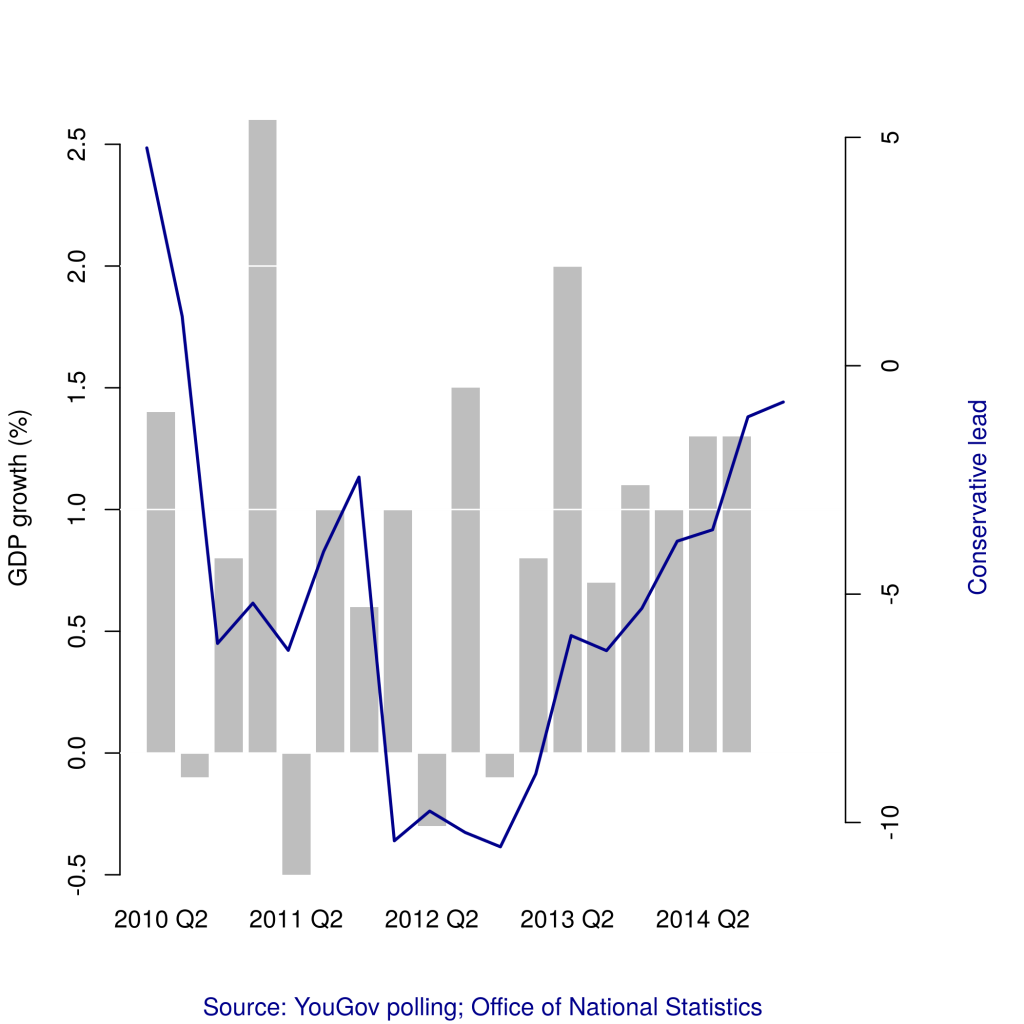

Nationally, there does seem to be a link between the performance of the economy and how the Conservatives are faring in the polls.

Here you can see the growth of the economy, quarter by quarter. On top of that, we’ve superimposed the Conservative lead in the polls, in the following quarter.

The Conservative lead – or, for most of this period, the Conservative gap to Labour – does track the state of the economy. After an initial honeymoon period, the Conservatives end up trailing Labour by more than ten percentages points in the middle of 2012 – a period which coincided with two quarters of negative growth. As the economy has returned to growth, the Conservatives have edged back up in the polls.

Locally

So, crude but suggestive evidence that economic recovery may help the Conservatives. But, as the Labour party has been keen to point out, voters don’t feel GDP growth directly: they feel its impact through the money that they receive in wages, or the income available to their household. So this election might not be decided by totemic and often-cited figures about GDP growth – but by something a little closer to voters: growth in earnings at the local level.

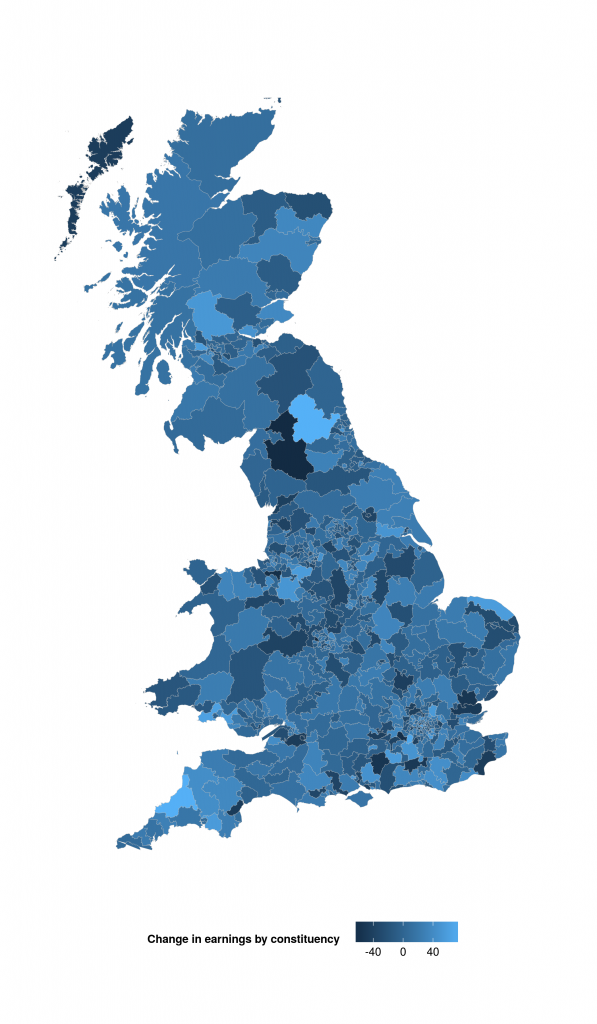

Fortunately, thanks to the government’s Annual Survey of Hours and Earning, we can get a picture of economic conditions in each constituency. The survey tracks different measures of economic conditions – but one of the most important is the average weekly income in each constituency. Because the survey is repeated each year, we can track not just the level of earnings, but also how those earnings have changed over time.

Between December 2013 and the most recent release in December 2014, the average constituency saw weekly earnings increase by £3.57. But in one of the worst-performing constituencies, Penrith, incomes fell by £69.8. And in one of the best-performing constituencies, Hexham, incomes rose by £78.7.

So the economic recovery isn’t being felt equally: there’s lots of variation between constituencies. But does any of this relate to how people vote – or are those patterns fixed?

The pay-off

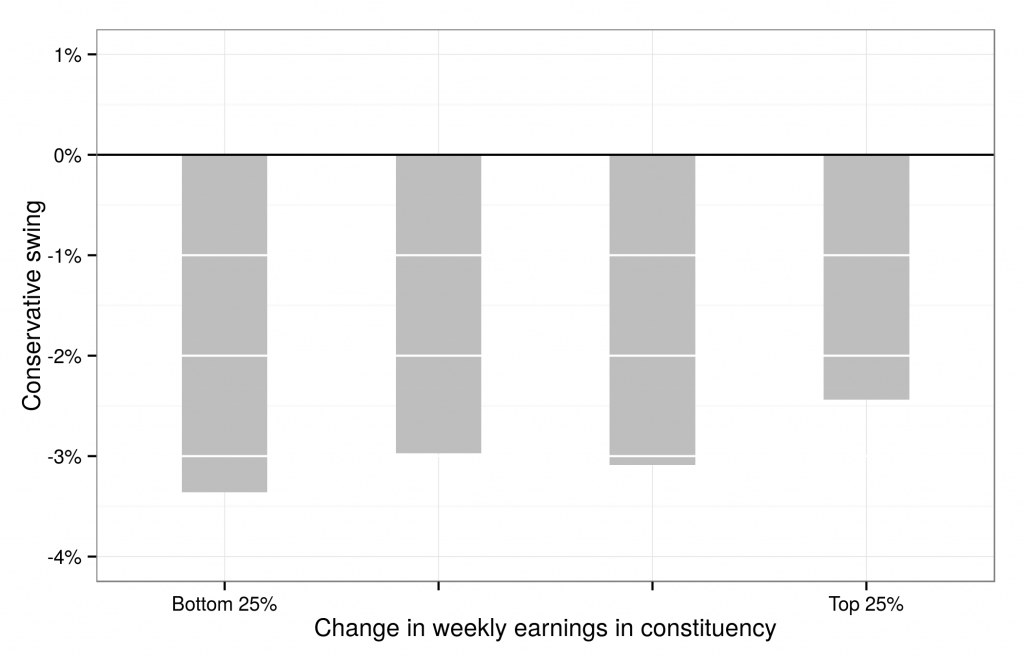

Let’s compare the change in earnings in each constituency to the electionforecast.co.uk forecast for the change in the Conservative vote.

What do we find?

In the bottom 25% of constituencies by this measure, there’s a swing away from the Conservatives of over three and a half percent. In the top 25% of constituencies, the swing is much less damaging – just two and a half percent.

we can be even more precise, and talk about the effect of extra earnings on votes. If turnout in 2015 were similar to turnout in 2010, then for every twenty pounds increase in earnings, the Conservatives get eighty extra votes.

That might not sound like much. It’s certainly not evidence that economic recovery will lead to a resounding Conservative victory.

But vote shifts like this can matter in close elections. In 2010, two seats – Hampstead and Kilburn and North Warwickshire – were decided by less than sixty votes. And the Conservatives will be hoping that current wage growth paints an ever-rosier picture as we get closer to the election.

There’s no iron-clad link between the state of the economy and the electoral performance of the governing party. In 1997, the economy was performing well – but that didn’t stop voters from delivering an almighty rebuke to the Conservatives.

But the Conservatives certainly see this as a key route to electoral victory. The Prime Minister has recently called on the private sector to boost wages. That might be good for employees – but on the available evidence, it would also be good for the Conservative party.

Technical notes

- The data on earnings come from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, made available on Nomisweb. We’ve taken information on gross median weekly earnings.

- The data on quarterly GDP growth come from the Office of National Statistics. We’ve taken series IHYN – quarter on quarter growth in GDP by current prices. We need to take the Conservative lead from the following quarter. That’s because we need to allow people time to react the state of the economy.

- The data on vote swing comes from electionforecast.co.uk forecasts, last updated on 2015-03-17.

- The link between earnings and the Conservative swing is not strong. The correlation between the two variables is 0.05, which is somewhere between a weak (> 0.1) and a non-existent association (0). Put impressionistically, an ounce of door-to-door canvassing would be worth a pound of bribing local employers to raise wages.

- We tested for a relationship between economic growth and changes in the Liberal Democrat vote share. There is no positive relationship: if anything, constituencies where wages grew more see a fall in the Liberal Democrat vote share.