Professor John Street considers the politics of copyright in the light of the Marvin Gaye/’Blurred Lines’ judgement.

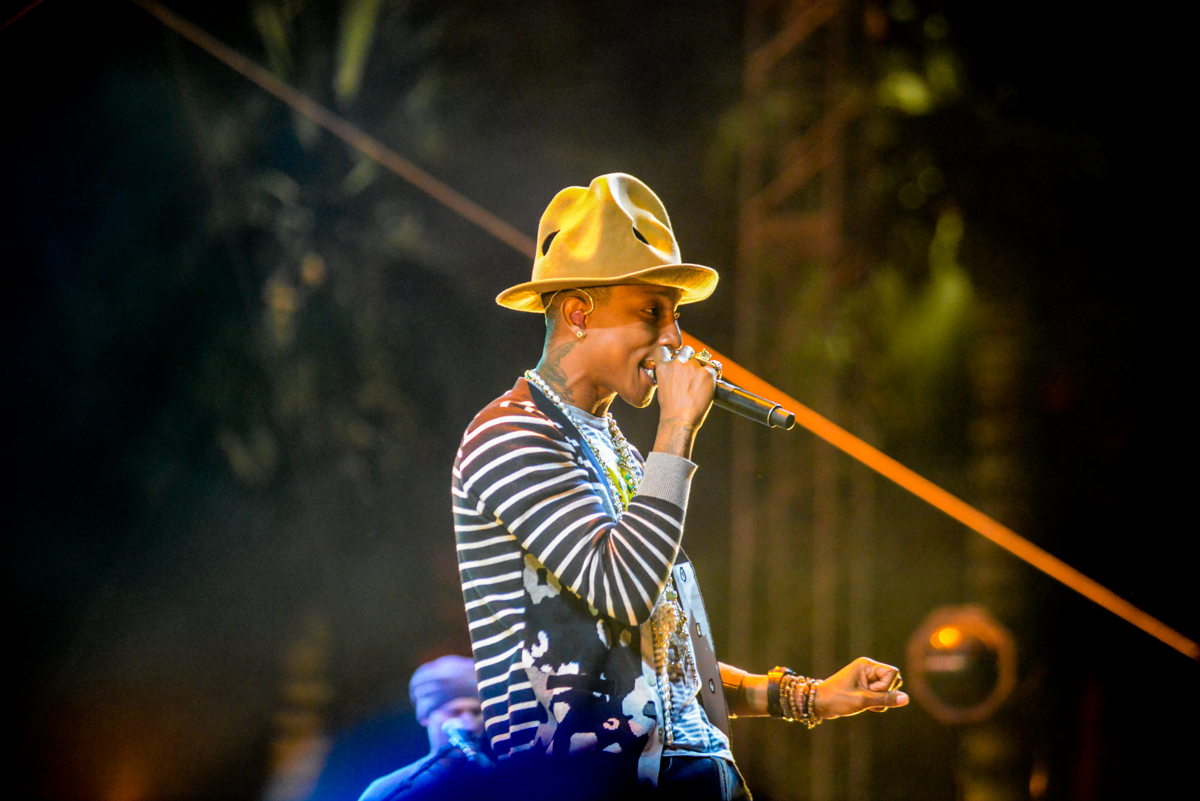

A cursory glance at the news coverage of the Marvin Gaye/’Blurred Lines’ case would seem to suggest one thing, and one thing only: that Pharrell Williams, Robin Thicke and Charles Harris jr/T.I. had plagiarised Gaye’s 1977 song ‘Got To Give It Up’ for their mega-selling 2013 hit ‘Blurred Lines’. Because of this, a US court decided that they owed Marvin Gaye’s family $7.3 million.

And a cursory listen to the two songs would seem to confirm that the jury was right: the two songs sound the same, especially the distinctive bass line and the use of the cowbell in the rhythm track.

What more is there to say? And what has any of it do with politics?

Well, a fair bit. The first is that the sound isn’t really the issue. This was not a case about illicit sampling, taking a recorded musical sequence and re-using it without permission or payment. This involves the copyright in recordings, but it was not at issue here. The issue was the composition, and the copyright in that. Here the similarity is, it seems, much harder to detect.

The musicologist Joe Bennett has convincingly argued that, in fact, the two songs have virtually nothing in common – not the lyrics, not the melody, not that bass line nor that cowbell.

The jury decided otherwise, and interestingly did so on the basis, not of the recordings, but the melodies (using sheet music) as played on a keyboard in court. They were asked to listen to the melody, rather than the sound. They decided the breach of copyright on this basis.

This is what the defence wanted. They had argued that Pharrell Williams was inspired by Gaye, as he admitted in interviews; he did not copy him. Indeed, there were wider issues at stake. Had the court ruled that the sound was copied, rather than the composition, they would have, in Joe Bennett’s words, have been determining that: ‘The act of putting an electric piano together with a cowbell and a 120BPM disco beat would need to have been judged a creative act in itself, making instrumentation and possibly even genre into protectable Intellectual Property. Which would have had massive implications for future creators of music.’ This is about the form of a culture and business of creativity and innovation.

Such decisions, and the laws on which they are based, are political in a number of important ways. They are clearly political in the familiar sense of determining who gets what, when and how. They are about the distribution of resources – $7.3 million. They are also about the distribution of rewards and status. While copyright law protects composers/songwriters, and sound recordings, it has not protected the individual musicians who may have added to the creative process – to those bass players and drummers who might make a sound ‘distinctive’. And the recent extension of the period (from 50 to 70 years) in which recordings remain in copyright has been seen as benefiting the recording industry (who can continue to lay claim to records from the mid-1960s), but restricting access to, and use of, musical heritage. And as Martin Kretschmer has argued: ‘72 percent of the financial benefits from term extension will accrue to record labels. Of the 28 percent that will go to artists, most of the money will go to superstar acts’.

At the same time, without copyright law, the incentives to be creative, or to support creativity, are compromised. And creativity matters to societies – it is valued by constitutions as well as by mere law. In China, recent reform of copyright law has been motivated in part by the desire to shift the perception of it as a nation of copiers rather than creators. But in drafting copyright law, policy makers have to steer a difficult course – along blurred lines – between protecting the creator while allowing for the opportunity to imitate and be inspired that creativity requires. This too is a matter of politics and political judgement.

John Street is a professor of politics at the University of East Anglia. He is currently conducting research funded by CREATe (the RCUK Research Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy). He writes this blog in a personal capacity.