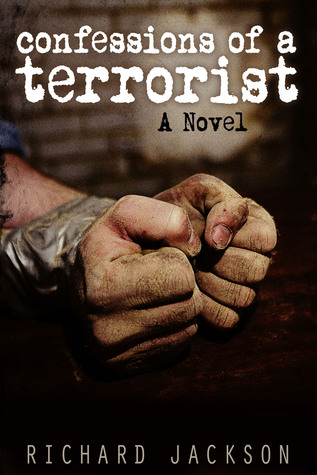

Professor Richard Jackson will be visiting UEA on 17 September to offer a guest lecture on his new novel, Confessions of a Terrorist. In the following interview with Dr. Lee Jarvis, he discusses the motivation behind writing this book, and its connection to his academic research on terrorism and conflict.

How would you summarise the plot of your new novel, Confessions of a Terrorist?

The plot of my novel revolves around a secret, redacted transcript of an interrogation of a notorious terrorist by an MI5 agent called Michael. The terrorist has infiltrated the United Kingdom and may be involved in a serious plot. Michael tries to get the truth out of him over the course of the night, but there is more going on than meets the eye. I chose to write the novel in this unique format for the simple reason that I felt it allowed the maximum opportunity for the ‘terrorist’ to fully explain himself at length – his motives, his beliefs, his life story. In the real world, we are hardly ever allowed to hear an actual ‘terrorist’ speak at length about him or herself. I also chose it because I felt that it would be a good vehicle for building tension, leaving clues and creating a series of narrative twists. I wanted the novel to be rooted in the thriller genre. The transcript, modelled on real secret transcripts I’ve seen, aims to give a sense of the secret world which ‘terrorists’ and spies are seen to inhabit.

You’re a longstanding scholar with a number of academic books and papers to your name – why decide to write a novel?

It was a very conscious and deliberate decision to write a novel about terrorism at a particular point in my academic career. I had never considered it before. After publishing eight academic books and dozens of articles, I realised that only a very small academic audience ever actually read my work and it had very little impact at all beyond the academy. I also noted that there were too few novels about terrorism that I could honestly recommend to my students as a way of animating and informing them about the subject. I therefore came to believe that writing my own novel might be a more effective way of reaching a wider audience and engaging my students.

How important was your academic background within the writing process, and did it make it any easier to write?

My academic background was crucial to the writing process, because I used my accumulated knowledge of terrorism and terrorists to fully inform the character development, plot, etc. At the same time, having an academic background actually made it very difficult to write a novel. This is because academic writing follows a very particular form, which in many ways, is antithetical to writing fiction. At the most basic level, as an academic you’re disciplined into writing in an abstract, authoritative, ‘objective’ manner, bereft of personality or human voice. You’re also taught to employ specialised jargon which fellow scholars in your own field can relate to. I had to leave all these ways of writing behind and try and find a more creative, human voice for the novel. In part, the choice to make the central character a former university professor was a way of trying to bridge these two ways of writing, the academic and the creative. I found it a really challenging and uncomfortable process. In fact, I still find the creative voice much harder than the academic voice, because the lack of formula immediately pushes you out of your comfort zone. I know exactly how to write an article by now, but where do you start with a piece of fiction?

What’s frustrated you most reading current fictional depictions of ‘terrorists’?

I remain puzzled by the failure of many contemporary novelists to depict ‘terrorists’ in an authentic manner. As far as I can see, most literary depictions of ‘terrorists’ are psychologically shallow, stereotypical and largely unconvincing – especially if you’ve talked to a former militant. In many respects, ‘terrorists’ have come to be viewed in the same way that paedophiles are – as a kind of pure evil, inhuman and without any redeeming human qualities. Consequently, it takes a very brave writer to consider depicting them in a humanistic or sympathetic light. The point is, however, even the most basic level of research would reveal that terrorists are not evil, inhuman, animal-like. I would have thought that some courageous novelists would have by now made a real effort to understand their subjects as real human beings – done some real research – and then narrated them in more authentic, more human terms. Sadly, we still don’t have anything meaningful on ‘terrorists’ in literary terms.

Why do you think fiction writers have struggled so much to accurately depict the psyche or motivations of a terrorist?

I think the primary reason for this particular literary failure is cultural and political. It’s a direct consequence of the operation of the powerful terrorism taboo. Particularly after 9/11, the atmosphere was so fraught and tense that public figures really had to self-censor and watch what they said. More broadly, it became taboo to even hear the voice of a ‘terrorist’, lest one come to understand and sympathise with their point of view. This is why, despite how important and prevalent this topic is, and how easy it would be to interview an actual ‘terrorist’, we almost never see direct interviews with them on television. In this context, writing a sympathetic literary depiction of a ‘terrorist’ would be akin to writing a sympathetic portrayal of a paedophile. Part of the taboo involves making sure one never gets contaminated by the views of a ‘terrorist’ or comes to sympathise with them in any way. The best way to ensure this is to never have any direct contact or pay attention to their actual words. The problem for the terrorism novelist of course, is that this means one can never really know one’s subject in a meaningful way. I think I can probably get away with writing against the grain like this because I have been writing critically about terrorism for years, and have a number of academic publications to back up the particular way I have constructed the ‘terrorist’ in my story. However, I expect that some people will still be upset at the way in which my novel violates the terrorism taboo.

What would make the novel a success, for you?

The novel is already a success, in my mind, because it has provided me with opportunities to speak in public forums and to particular audiences that my academic writings to date have not so far allowed. More broadly, if I could reach an audience beyond the walls of academia and make readers think critically about how our society has responded to the threat of terrorism – in large part because of the way in which we’ve constructed the ‘ evil terrorist’ – then I will consider the novel a great success. Most simply, I am hoping that it will contribute to public debate on issues of real ethical import, and perhaps be part of other factors that one day lead to progressive policy change.

Professor Jackson’s talk is titled Terrorism, Taboo and Discursive Resistance: The Agonistic Potential of the Terrorist Novel, and hosted by the School of Politics, Philosophy, Languages and Communication Studies, and the Critical Global Politics Research Group. It takes place on Wednesday 17 September 2014 at 4pm in UEA, Arts 2.01. All are welcome.

Photocredit: KamrenB Photography